Point of View: Riding the POV

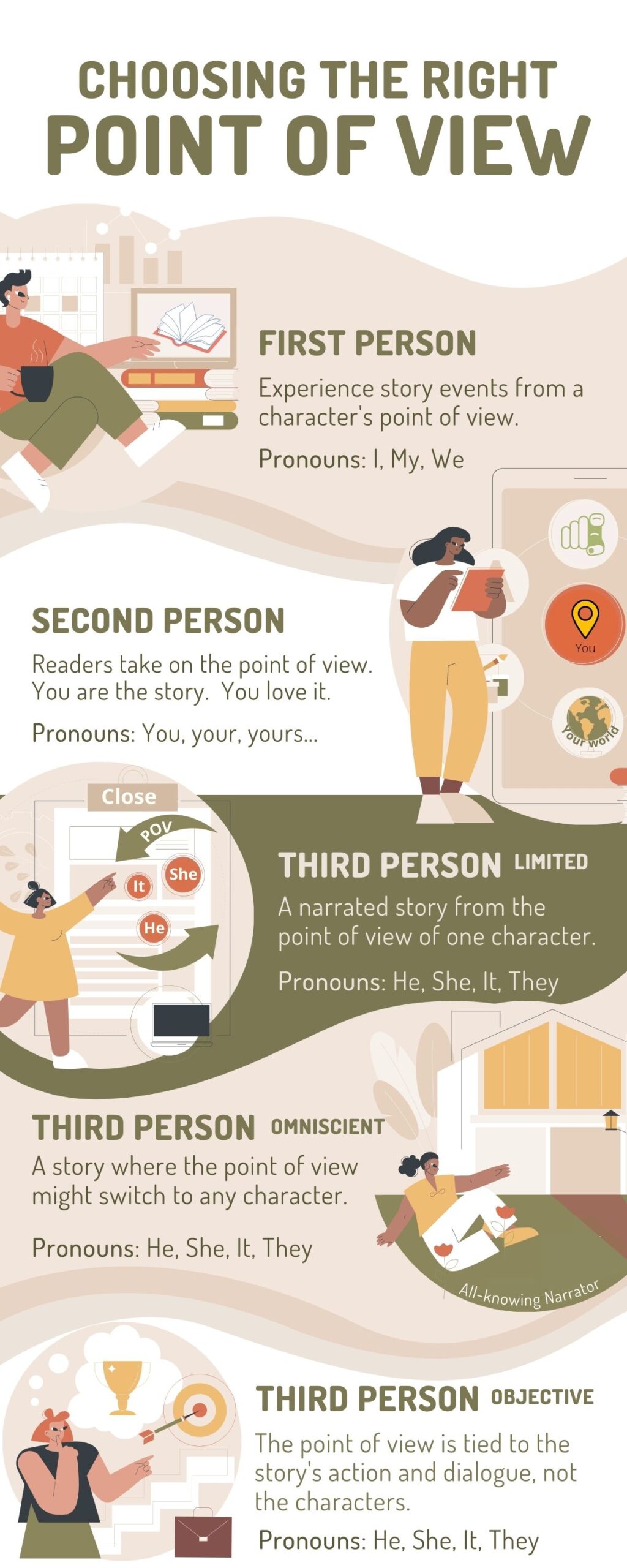

Every story has a point of view (POV). What does it mean? It means, the author has to have a strategy that lets the reader know whose story it is at every turn. From the opening lines to the last words an author must ride the POV.

The Point Of View

A POV fixes the story viewpoint at the start. More often than not, it means we get to know what at least one of the characters thinks or feels. When writers do POV right, they put the readers into the head of one or more character or if desired, keep them out. Whatever the choice, writers must stick to the POV plan from start to finish. Remember, unsuspected POV shifts upset readers. Don’t do it.

Whenever I start a new story, my first inclination is to use third person limited. It’s my favorite POV. No matter where I end up, first person, or a form of third person, I push myself to ride the POV.

What is Riding the POV?

Riding the POV means no deviations from the intended story perspective. Your story must answer four questions:

- Who is speaking?

- Who is seeing the story action?

- Is it possible to get into the characters head?

- What is the narrative distance?

Shaping these four questions into a successful piece of fiction requires the writer to think through the direction of their story. Once you make these decisions, the next step is to jump into it. Just ride the POV.

Know the Speaker

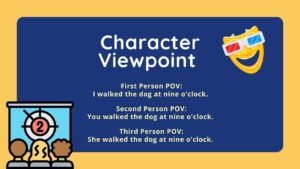

In first person, your character narrates the story giving a first-hand account of the action. When you use first person, the narrator knows everything about themselves. They are also able to share what they see, hear, feel and think. Outside of their own experience they are mere observers. First person characters can guess at, wonder about or fear what another character knows, thinks or feels, but they can’t pop into other heads to say how another character feels. For example, take these accounts from a character:

I saw the man come inside holding a gun and my heart skipped a beat. He was thinking about killing me. (the narrator can’t know what the man was thinking)

I saw the man come inside holding a gun and my heart skipped a beat. I knew I was dead.

(Here the narrator sticks to their own thoughts and feelings)

I saw the man come inside holding a gun and my heart skipped a beat. He looked straight at me, seeming angry and steamed up. I just knew I was dead.

(This works because the narrator makes an assumption based on observation without entering the character’s head.)

No matter which form of first person you choose, the same rules apply. Don’t stray away from what the narrator can believably know or observe.

There is more flexibility in third person point of view. That means, there’s also more room to mess up. Make a plan. Whether you have a single or multiple viewpoints story it’s still important to give the reader a sense of whose story it is. It can’t be everyone’s story. Pick your protagonist. Once done, make sure that as much as 70% or more comes from that character’s viewpoint. Let the reader know what the main character thinks, feels and make sure the action happens around or because of them. On the other hand, if your story has a neutral narrator be sure to use action and dialogue without drifting into the characters heads.

Third Person POV

Let’s look at a writing example from third person limited / omniscient to compare with third person objective.

Dorothy woke early that morning. The alarm hadn’t sounded, and she felt tired but decided to get up anyway. Her whole body ached. How would she get through the next few weeks without him? She made herself breakfast, but it turned her stomach, and she couldn’t eat. Feeling desperate, she called her mother.

“I miss him,” she said when her mother answered.

“Of course, you do. How are you feeling today?”

“Just awful. It’s not fair. I want to die too.”

Third Person Objective Writing Samples

Dorothy woke early that morning. The alarm hadn’t sounded but she got up anyway. She moped around for at least an hour and finally made herself some breakfast. With her breakfast untouched, she called her mother.

“I miss him,” she said when her mother answered.

“Of course, you do. How are you feeling today?”

“Just awful. I ache all over. It’s not fair. I want to die too.

Although, it’s obvious from Dorothy’s actions that she is sad, the reader has no confirmation of what the character thinks or feels until she speaks with her mother. At that point, the reader gains insight through the dialogue. In third person objective, the author must stay out of the character’s head and most of all, let the reader gain insight based on the action. For more on writing dialog read 3 Ways to Improve Your Dialogue

Through The Character’s Eyes

In your stories the reader must know who is seeing the events as they happen. In first person it’s the narrator, but they can only know what’s happening around them.

Jane was sad. In the kitchen, she started telling her mother about breaking up with John.

(Unless the narrator is in the kitchen, they can’t know anything about Jane)

The example above shows how the point of view shifted away from first person to third person omniscient. Writing in first person makes it easier to stick to your character’s perspective. Still writers make mistakes. That’s where editing comes in. Edit out any POV shifts.

I knew Jane had been feeling down. I went into the kitchen to check on her. A moment later, she started telling her mother about breaking up with John.

(fixed)

The who is seeing mandate can get confusing in third person. That’s why it’s so important to have an authorial process mapped out at the start. Ultimately, you want to make sure the reader can follow any POV character shifts. In third person multiple viewpoints, some authors do this in chapters, some using parts or time periods and others use scene breaks. It really doesn’t matter when the POV shifts. What matters is that the reader doesn’t get confused.

Personally, I’m not a fan of multiple viewpoints. Yet, I’ve read many books that use the technique. Some do it well. Even harder to manage is point of view shifts in third person omniscient. The narrator knows, sees, hears and feels everything. The ability to do that might cause some writers to head hop. Now, that can get downright confusing. Know whose story it is and know who’s scene, chapter, or part it is too.

Getting into the Characters Head

This is an easy one. If you use first person peripheral, the narrator can relay his thoughts and feelings, but he can’t get into the heads of the other story characters. A classic example is The Great Gatsby by Scott Fitzgerald. The narrator, Nick Carraway shares his thoughts and feelings, but only speculates about what the protagonist, Jay Gatsby thinks or feels. Here is an excerpt.

And as I sat there, brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come such a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close he could hardly fail to grasp it.

Notice the narrator’s words when he speaks of Gatsby. For instance, he says Gatsby’s wonder, something the narrator observed. When it came to feelings Nick says of himself that he was brooding, that’s being in his own head. On the other hand, he says Gatsby, must have seemed. In this example, the author kept the proper perspective. The first person narrator stays in his own head.

Things get even simpler for third person objective. You can’t get into the character’s head. That’s all there is to it. Check out Hills Like White Elephants’ by Ernest Hemingway. It’s a short piece of fiction, but there is no insight into what the characters feel. From the prose we get a since of where they are and why they’re there. Nothing is explained. Whatever the reader picks up, is what the reader picks up. If done well, the reader will get the meaning as the author intended.

In my mind, third person objective leaves a lot to be desired because it’s not possible to feel close to the main character. Everything depends on the author’s intent. When you write, know how your point of view works, and you’ll get the story you desire.

Point of View & Narrative Distance

Narrative distance determines just how close the reader feels to the characters. It relates to POV because how an author shows emotional or relational distance is intwined with the limitations of the POV. In all but third person objective POV we can get right inside the character’s head, or dare I say into their bodies.

A close up: Crossing the room, his heart pounding, his hands shaking, he smiled and then stood next to her.

Let’s move out a bit: He cautiously crossed the room, feeling eager to stand next to her.

Let’s move out more: He crossed the room to stand next to her.

Zooming in or out can vary throughout the story. However, distance shifts shouldn’t happen haphazardly. If your story has been very impersonal and then suddenly without warning or progression to that point, you shift the distance, it will upset your readers. The intimacy or lack of it should feel natural and work with the type of story you want to tell. Sometimes, authors use present tense to bring the reader close to the story. A few books that used this strategy are The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins and Normal People by Sally Rooney.

There you have it. POV is a multi-leveled thing. Ultimately, you need a plan that answers the four point of view questions we discussed in this post. Once done, ride the POV from start to finish.